6 min to read

On the Design of Software Organizations - Balancing Autonomy with Governance

With a spurt in the documented history of any field of endeavor, we will begin to discern some recurring cycles of patterns. What was once touted as the next best thing would have been subsequently denounced only to have it revive later like the proverbial Phoenix with even more vigor. This observation is conveyed by the old chestnut about “history repeating itself”. In the software world, with a decade witnessing the kind of events that used to take a century or more to happen, this phenomenon is even more palpable. This whole cycle of a pattern being raved about, ranted on and re-raved subsequently happens in less than 5 years sometimes.

In this post, I am going to talk about one such pattern which I personally had a chance to advocate in one big organization recently. It is about the growing need for autonomy for product teams.

STAGE ONE - PRODUCT PROLIFERATION

Several years ago, (in the 1980s and 1990s ) every group in an organization wanted to develop their own software. Each group of course religiously avoided discourse with others and started to form products that are suited for the needs of the group in question but studiously avoided any interactions with other products. Soon we had CRM systems, billing systems, hiring systems, supply chain systems, ecommerce systems etc. With the consequent proliferation of software products in the enterprise, someone came down with a heavy hand and usurped software development from domain groups. This lead to:

STAGE TWO - THE IT POLICE

We had all kinds of IT police. An Enterprise Architecture team. A central build team. One team that develops all IT artifacts in the enterprise. One team that dishes out requirements for all IT systems in the enterprise. Domain knowledge was marginalized. The specialized softwares were augmented and sometimes replaced by huge “enterprisy” systems that did too much work - inefficiently! We had 2000 page design documents, unwieldy monolithic software solutions, 3 year waterfall based development cycles with zilch feedback and so called “architects” who dabbled in power points and relied on automated code reviews to produce 100 page code reviews.

STAGE THREE - THEN CAME THE DAWN

By circa 2000, it was evident that this trend hindered growth to a crawl. Too many things were being combined and the Single Responsibility Principle was honored in the breach. Teams were no longer efficient to catering to the needs of the particular domain.

Then agility arrived in the scene. Small systems got back into fashion. Self organized teams composed of a handful of people were able to demonstrate value in small increments. People realized that

Any organization that designs a system will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

This observation codified as “Conway’s Law” by Fred Brooks became the new mantra. Organizational design, it was realized, influenced the design of software. Hence functional groups owning discreet pieces of software got back into vogue. But this trend though outwardly resembling stage one is still distinct from it. The self organized groups could do end to end designs, write code and take care of operations. Most importantly, the software developed is “ecosystem aware”. It knows how to interact with other softwares that exist within the organization. In short, contracts between different applications need to be documented, versioned and supported. This important distinction makes the new model more successful than it was in stage one.

RECOMMENDED ORGANIZATION DESIGN

Increased Autonomy

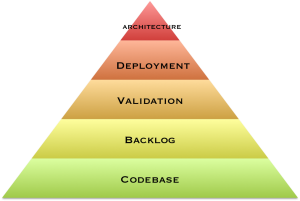

[caption id=”attachment_1015” align=”alignleft” width=”300”] Autonomy Pyramid[/caption]

Autonomy Pyramid[/caption]

The learnings from these have taught us to design better organizations. Functional self contained product teams need to be counter balanced by the appropriate amount of governance. The teams could be broadly classified as product teams and enabling teams. Product teams are self organized teams that develop specific products whilst the enabler teams provide the appropriate level of cadence and governance to ensure that the product teams don’t get off the rails.

The autonomy pyramid is shown here. Autonomy starts when the team has the ability to own its own code base - i.e. it has its own SCM repository. The autonomy increases when the team starts owning its backlog i.e. it is able to interact with the business, make prioritization decisions on the features that need to be implemented etc. If the team has the ability to validate its changes, it will feel further empowered. Now the team can make the appropriate changes and be sure that it is not affecting other systems. Further autonomy is acquired if the team owns its deployment. It would then be in a position to deploy its software independent of other teams. The final stage of autonomy is achieved when the team is able to influence its own architecture. Stefan Tilkov talks about the Guardian effort to break the monolith in this video. He is able to create self organized teams that can own their architecture provided they are compliant with the contracts between the different applications. We can potentially have teams using Rails, Python, Scala with Play and Java applications co-existing within the same ecosystem.

Governance

But there are a few questions that are unanswered if we focus only on autonomy. How can the organization benefit from the latest innovations in DevOps and Continuous Delivery? How does it make sure that the system gets validated to comply to the contracts that have been agreed upon across different teams? How can we be sure that in the pursuit of the ultimate framework, we don’t discard long term visions of architecture?

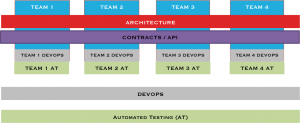

These questions lead to a system of governance that is getting increasingly popular within many organizations. There are functional teams like team 1, team 2 etc. as shown. There are also enabling teams such as architecture team, contracts team, devops and Automated testing (AT) teams. Some of these teams are virtual i.e. these are not separate teams but made of people from the existing product teams. For instance, there does not have to be a dedicated team for architecture. Instead, it can be composed entirely of architects extracted from team 1 through 4 in the above example.

These questions lead to a system of governance that is getting increasingly popular within many organizations. There are functional teams like team 1, team 2 etc. as shown. There are also enabling teams such as architecture team, contracts team, devops and Automated testing (AT) teams. Some of these teams are virtual i.e. these are not separate teams but made of people from the existing product teams. For instance, there does not have to be a dedicated team for architecture. Instead, it can be composed entirely of architects extracted from team 1 through 4 in the above example.

However, there are other teams such as Devops which require specialized knowledge of various innovations and products that are present in the space. Hence it is a good idea to have DevOps specialists in the enterprise. These folks need to be seeded back into the actual product teams so that the team continues to be autonomous. This model addresses both the concerns effectively. I have seen this model adopted in multiple big enterprises of late.

Comments