8 min to read

Mockery

Mocking - Introduction

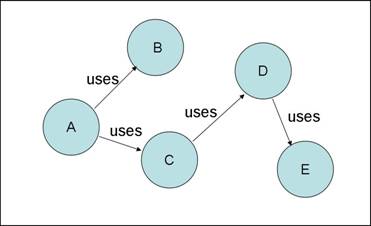

Objects are first rate citizens in the Java society. Like a typical society the Java world has different flavors of objects each performing its own function. The Single Responsibility principle (SRP) states that objects should perform one single responsibility to ensure maximum re-use. This principle, however sociologically sound poses huge testing challenges. The problem with it is that objects can no longer be tested in isolation. The entire dependency tree of objects needs to be materialized before an object can be tested. Mocks are an attempt in the direction of faking object dependencies. The object being tested can be tested by mocking its immediate dependencies.  In the diagram above, for the object A to be tested, we need to materialize the entire chain of dependencies which means we need to create classes B,C,D and E. If one of the objects tested relies on the services of a container, then it becomes harder to test in the absence of a container. Mock objects serve the following needs:

In the diagram above, for the object A to be tested, we need to materialize the entire chain of dependencies which means we need to create classes B,C,D and E. If one of the objects tested relies on the services of a container, then it becomes harder to test in the absence of a container. Mock objects serve the following needs:

- They mimic the behavior of normal objects so that the object being tested does not know that it is interacting with the mock object.

- They mimic container behavior. A thinks it is interacting with a container but instead is interacting with an entire mock framework that apes what the container does. In the example above, B and C would be mocked by mock objects. This ensures the following:

- A can be tested without relying on containers.

- The dependencies D and E dont have to be materialized since the mock objects B and C dont have dependencies of their own.

Strategies for Mocking

Writing Testable Classes.

A class that can be tested with mocks should be testable. This means that it has to allow the user of the class to replace an implementation of its dependencies with mock dependencies. Conside the following class:

public class A {

public void foo(){

B b = new B();

// do something with B

}

}

This class is very difficult to test with mocks because it is instantiating B within a method. Hence we cannot replace B with a mocked instance of B. To make this class testable it can be coded as follows:

public class A {

public void foo(){

B b = createB();

// do something with B

}

protected B createB() {

return new B();

}

}

This version of the class is better but still not perfect. The reason that it is better is because it is possible to instantiate a sub class of A with the createB() method over-ridden.

public class TestA extends TestCase {

public void testFoo() {

A a = createA();

a.foo();

}

public A createA(){

return new A(){

// over-ride createB() method in class A

protected B createB() {

// create a mock version of B and return.

}

}

}

}

The version of A that would be the most testable would be the one where B’s interface is used instead of the actual class B. The most testable objects are the ones that use principles such as IOC (Inversion of Control) to facilitate the injection of dependencies in them.

How do mocks work

So what exactly is this mock object all about? How does it ape what other objects do? They say “monkey say monkey do” and this is applicable to mocks as well. The following steps need to be followed in using mocks:

Create the mock object.

If the object to be mocked is a class(as opposed to an interface), it is possible that we might have to provide constructor arguments and values for using non default constructors.

Set the expectation.

This means that the mock object might have to be told as to what methods in it will be called, how many times they will be called and in what order. We also need to specify with what arguments the function would be called and how to match these arguments with the actual arguments passed. Ex: Consider the following class:

public class ClassToBeMocked {

public ClassToBeMocked(String arg0){

}

public String method1(int arg0, String arg1) {

--

}

public int method2(String arg0){

--

}

}

This class needs a String argument to be instantiated. Accordingly that needs to be passed during the creation of the mock object phase. In the set expectation stage, we can indicate that method1 would be called exactly once with arguments 10 and “foo” and method2 would be called twice exactly with arguments “bar”. The way these expectations are set differs from one framework to another. The [JMock|http://www.jmock.org/getting-started.html] framework gives extensive control on argument matching. For instance, see the [constraints|http://www.jmock.org/constraints.html] that can be set.

Set return Values

In this phase, we tell the mock object what value to return when the constraint is actually called. For instance, in the above example we can specify the mock object to return the string “John Doe” when method1 is called with arguments 20 and “foo”. We should also be able to say here that method1 should always return the string “John Doe” no matter what arguments are passed to it.

Actually execute the tests using the mock objects.

At this stage, the actual tests are run.

Verification

The mock objects may be explicitly called at this stage to verify if indeed they have been called with the correct number of arguments in the order specified.

The Denizens of the Mockery Zoo

A lot of frameworks exist for writing mocks. All of them rely on method interception which is achieved in Java in a couple of ways:

- Code generation.

- Interface and class interception. Code generation is not a preferred approach since the code needs to be re-generated when the actual class changes. Also the test class needs to rely on mock code that has not been written (it is going to be generated in the build). Hence frameworks that utilize interface and class interception techniques are by far more popular in the world of mockist monks (yeah mocking is almost a religion in certain parts of the java landscape). The two frameworks that have their own dedicated areas in the mockery zoo are:

- JMock

- EasyMock Easymock scores due to its simplicity and its support for code completion. The following articles compare the two frameworks:

- JMock vs. EasyMock

- JMock vs EasyMock by the JMock people Here is the broad view echoed by these and other articles. Feature: Documentation JMock: Decent EasyMock: Very good Feature: Arguments matcher - i.e. the way we specify how arguments passed should be matched JMock: Hard to use but extremely flexible. EasyMock: Easy to use. Less flexible. But it is possible to create our own argument matchers if the need arises. Since in most cases, we dont need to use complicated argument matchers this should not be a limitation. Feature: Code completions, Refactorings etc JMock: Hard since the actual interface is not used in specifying the mock criteria EasyMock: Works well with most IDEs since the actual interface is used Feature: Ease of use and understanding JMock: JMock is loved by the proponents of literate programming. This is because the expectation setting phase in JMock resembles a specification very closely. But to a developer, it is cumbersome to have to remember so many method calls and write this explicitly. EasyMock: EasyMock is very easy to use since the actual method is called with the correct parameters during the expectation setting phase of preparing the mock.Since 2.2, EasyMock has become much more literate also with effective use of generics and static imports.

Comments

Daisy: Hi Is there any way that I can pass constructor arguments while creating the Mock Objects using Jmock 2.X? If no, How can we pass the arguments of the constructor then? Thanks in advance Daisy

raja shankar kolluru:

Comments