8 min to read

App Optimization - Asynchronous Pre-fetching Strategies

I remember perusing through an article on web services some time ago where the author quips about the similarity between web services and teen sexuality. He said that in both cases, they talk more about it rather than do it and even if they do it they do it pretty bad. A similar comparison can be drawn with pre-fetching.

Pre-fetching is one of those things that sounds almost cliched in that everyone talks about it. But I have seldom seen good implementations. How do we know what to pre-fetch? And when would be an appropriate time for that? Who owns the pre-fetching thread? I recently embarked in an application optimization exercise. As part of that, I had identified some candidates for being pre-fetched. How I went about implementing pre-fetching forms the rest of this article.

A Pre-Fetching Use case

Let us illustrate this with a use case that showcases the virtues of pre-fetching. Consider a rather lengthy sequence of operations in the process of rendering a banking portal page. The steps are explained below along with the time taken for executing each step.

Obtain user profile. (20 ms)

Find the accounts linked to the user. (savings, current, credit card, deposit, demat etc.) (100 ms)

Obtain balance information for each account. (100 ms * 5 for a user with 5 accounts = 500 ms)

Fetch any status alerts for each of the user accounts. (100 ms)

Let us assume that page rendering takes about 200 ms (including network latency, page rendering etc. ) This is usually much higher but condensed here for illustration purposes. AJAX interactions are faster and are assumed to take just 60 ms to complete rendering.

Let us say that we need to implement this functionality with an AJAX enabled web page. The page is implemented using HTML with DIV elements for obtaining account balances and for displaying status alerts. Each DIV individually seeks out services that deliver the relevant content using AJAX. The obtained information is then printed by the respective DIVs. This entire process can be depicted by the following sequence of events:

- First retrieve user profile. (20 ms) = 20 ms

- Paint the screen. ( 200 ms) = 200 ms

- Use AJAX to obtain and display status alerts. (100 ms + 60 ms to render the alerts) = 160 ms

- Use AJAX to obtain and show balance information. ( 100 ms (to obtain the accounts) + 500 ms + 60 ms for rendering) = 660 ms

- Total time taken to render the page = 20 + 200 + 660 ms ( the 160 ms is concurrent with the 660 ms and hence would not be counted) = 880 ms

We can implement this in an optimized manner using pre-fetching. The steps are as follows:

- First retrieve user profile (20 ms) = 20 ms

- Obtain all accounts for the user. ( 100 ms) = 100 ms

- Fire pre-fetch calls for every one of the accounts to obtain balance information and for status alerts. ( 0 ms)

- Paint the screen (200 ms) = 200 ms

- Use AJAX to obtain status alerts ( 60 ms to render the alerts + 0 ms for obtaining the the alerts since they have been pre-fetched)

- Use AJAX to obtain balance information. ( 0 ms to obtain the balance information + 60 ms for rendering) = 60 ms

- Total time taken = 20 + 100 + 200 ms + 60 ms (one for status alerts or balance since both are concurrent) = 380 ms

Quite clearly, prefetching enabled us to save a whopping 500 ms! This situation illustrates the immense optimizations that are possible with pre-fetching. So how is this entire process made possible? This is discussed in the rest of the article.

A Caching example

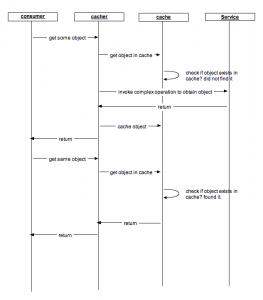

Pre-fetching is greatly facilitated using caching. Consider the caching sequence diagram below:

This is a fairly straight forward implementation of a caching strategy. The consumer calls a service to obtain an object. The object retrieval by the service mandates a lot of expensive computation. The service call is intercepted by a cacher which first checks if the object exists in a cache. If found, it then returns the cached object. Else, it calls the underlying service to obtain the actual object and in the return path caches the object. When a consumer (it can be the same consumer as before or a different one) next makes a call to obtain the same object, it is available out of the cache.

This is a fairly straight forward implementation of a caching strategy. The consumer calls a service to obtain an object. The object retrieval by the service mandates a lot of expensive computation. The service call is intercepted by a cacher which first checks if the object exists in a cache. If found, it then returns the cached object. Else, it calls the underlying service to obtain the actual object and in the return path caches the object. When a consumer (it can be the same consumer as before or a different one) next makes a call to obtain the same object, it is available out of the cache.

This sequence illustrates a reactive strategy to caching wherein all the objects are not cached upfront - only those that are asked. If the consumer never asked for an object with a particular key, it would never ever get cached. Reactive caches serve well when the number of objects to be cached is immense. Reactive caching also works when “cache staleness” is a problem i.e. when the underlying object can be potentially updated without updating the cache.

Optimized Second Calls

The caching example highlights a situation when a second call to a service is automatically optimized by virtue of the first call. This is typically achieved because of caching as is discussed in this particular case. But it does not have to be restricted to caching. It can also happen in multiple other situations. Let us take an example of a “learning” querying service. It accepts a query and returns a result set based on the criteria passed in the query. However, the querying service can “learn” from the query by indexing the result set using the criteria passed so that if the same type of criteria are passed again, the query would perform much better. In this case too the second call would be more optimized than the first.

So here is a fairly simple pre-fetching surmise:

If a similar second call to an operation is more optimized than the first call, then the operation in question can benefit from pre-fetching.

The assertion above needs more qualification.

What do we mean by the similarity between the first call and the second? Does the second call have to pass the exact same parameters as the first one? Or does it have to pass the same kind of parameters? In most cases, the expectation is that the first call and second call need to be identical! So if the first call invokes an operation “bar” on service foo with a string “123” then the second call needs to exactly do the same thing.

But in the indexing example that I alluded to above, it is possible that the two calls be similar rather than be identical. For all practical purposes, we would discuss only situations where the first and second calls are identical since this case is more typical. I call a service that behaves optimally for a second call as an optimize-able service.

Strategy for Pre-fetching

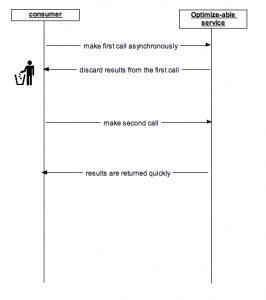

The pre-fetching strategy is illustrated in the sequence diagram.

The consumer first calls an optimize-able service asynchronously. The results obtained from the service are discarded . The second call is then made at the appropriate time. Since the service is optimize-able, the call returns faster. All this is done transparently since the callee is not aware about the nuances of pre-fetching the first call. All it knows is that the service has returned faster!

It is possible to use the asynchronous execution wrapper that was discussed in another article to implement the pre-fetching strategy as enumerated above. Here is a snippet of code that accomplishes it. Let us assume that we have a class called FooServiceImpl which implements an interface called FooService defined as follows:

public interface FooService {

public SomeVO bar(String id);

}

The client code can pre-fetch it as follows:

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(1000);

FooService fooService = new FooServiceImpl();

FooService asynchFooService = AsyncExecutor.getInstance(FooService.class, fooService, executor);

asynchFooService.bar("123"); // do pre-fetches

// later on execute the actual call.

fooService.bar("123");

The call t0 fooService would be much more optimized.

Comments

Gaurav: Hi Raja, There is another interesting scenario in case of prefetching caching (cache warming) worth considering, for example the application is clustered. The async wrapper has to make sure the cache warming or prefetching caching happens in one and only one machine. (hence I am assuming our caching is distributed caching) Cheers, Gaurav Malhotra

raja shankar kolluru: Yes that is a scenario that we do need to consider. But I am assuming that we delegate the responsibility of fetching in the “correct” node of the cluster to the caching mechanism. This way, our pre fetching logic is independent of our choice of clustered or non clustered caches. If the cache is non clustered, then we pre-fetch locally. if it is clustered, then we pre-fetch closest to the consumer i.e. in the same app server as the request and then by virtue of clustering, everyone else gets to benefit from it. One obvious thing is that pre-fetching itself is the default if we do pro-active caching since all the rows are pre-fetched anyways.

Comments